CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Helping the previously incarcerated obtain employment

U.S. has the largest official prison population in the world. And among the 620,000+ people released each year, one third will return to prison at some point. While there are many causes for recidivism, unemployment proves to be one of the most influential.

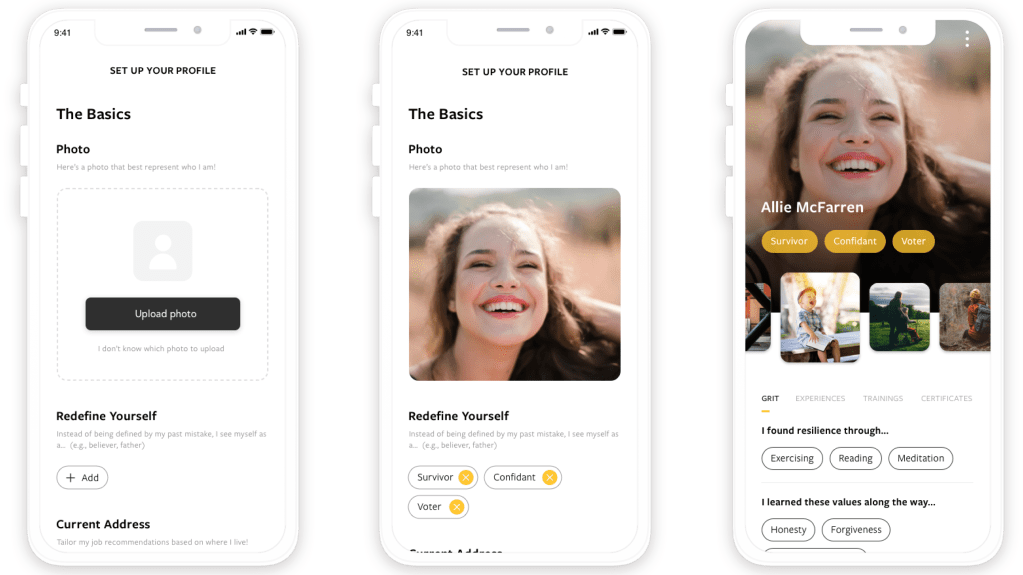

With the overarching goal of breaking the cycle of incarceration, we designed an app that allows the previously incarcerated to demonstrate their true selves and shared humanity during their job search, directly addressing employers’ tendency to dehumanize them based on their criminal record.

Before we design the solution, we need to understand the problem.

We conducted market research to gain a basic understanding of the current narrative, trends and policies around hiring the previously incarcerated. Competitive analysis helped us understand what part of the problem they are trying to solve. We then leveraged one-on-one interviews to deep-dive into the needs, pain points, motivations and behaviors of both groups of users. We reached out to support programs, placement agencies and other intermediary players in the field that can provide crucial insights on both the employers and job seekers.

Our research provided unique insights into the type of barrier the previously incarcerated individuals face in the job market:

Even when inherent barriers such as habitual behaviors and lack of qualifications don’t exist, an external barrier persists in the form of employers’ unwavering prejudice.

Design to tackle prejudice

Despite my time in prison, I considered myself trustworthy and responsible — the type of guy who would get the job done. I figured that desire — the willingness to work hard — would earn me a job, but failed to account for the discrimination ex-cons face…All people saw was that criminal record.

Seth Ferranti, Source

1. Change the language

“Felons, jailbirds, ex-convicts”…The narrative surrounding people with records are inundated with epithets. Some of these crimes have been decriminalized in the recent years but the societal language has remained the same. This persistent act of labeling reduces people to their crimes, and, as a result, they are seen as criminals and nothing else. It perpetuates the stigma. By allowing individuals to redefine themselves, we introduce a lexicon of identity that reveals their shared humanity, which serves as a medium for connection and empathy, allowing the space for their true selves to emerge.

The use of epithets also limits an individual’s room for growth and change by forcing them to see themselves the same way. According to the U.K. Ministry of Justice report, Transforming Rehabilitation, people are less likely to recommit if they define themselves in ways beyond their mistakes or the epithets.

2. Revert the social construct of incarceration

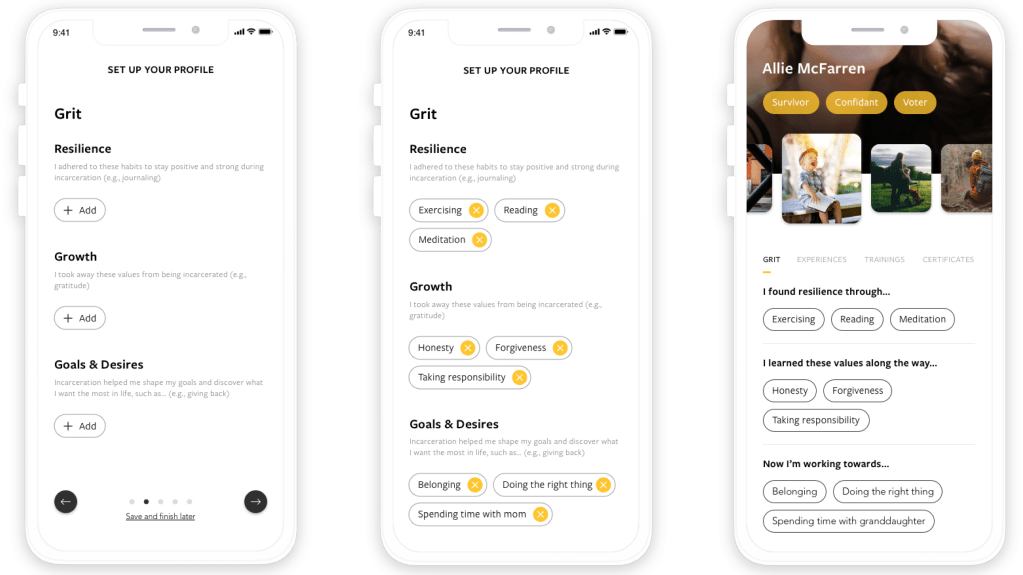

An individual that came out of incarceration looking for help or ways to secure a job “shows us that they are committing to making a change” (interviewee). Emerging with this sense of commitment from a “dehumanizing” environment characterized by overcrowding, violence and enforced solitude requires a tremendous amount of resilience, creativity, hope and perspective, or, in other words, grit.

Unfortunately, grit isn’t something people typically associate with incarceration, nor is it a quality that the job seekers themselves naturally identify with due to the cultural emphasis on education and professional experience. However, this cultural emphasis has begun to shift: not only is there research concluding grit as a significant predictor of success, there are also employers that have started to look for “accomplishments that fall outside conventional rubrics” (source).

Thus, helping job seekers communicate their grit accomplishes two things. One, it injects a note of positivity and hopefulness into the societal concept of incarceration. Two, it reveals the strengths and qualifications of job seekers to both the employers and themselves.

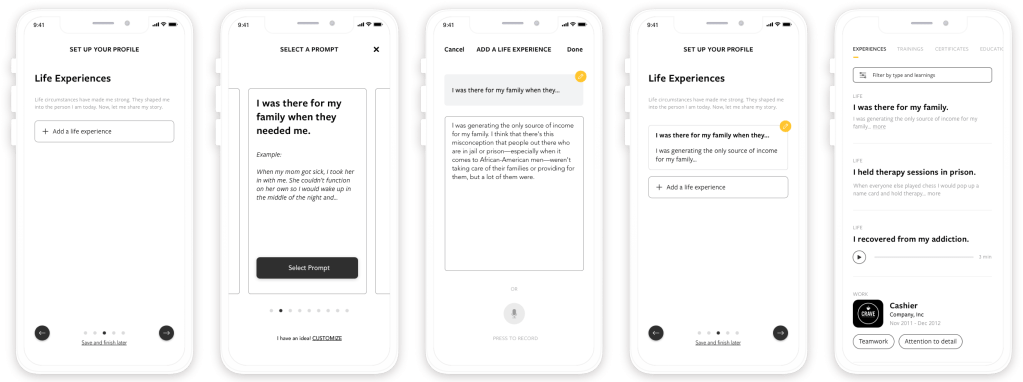

3. Humanize through storytelling

When we asked an interview participant about what factors increase employers’ willingness to hire the previously incarcerated, he said it all comes down to “just having that conversation”. Studies show that we judge someone more leniently for an offense when we know the details of their story. So, how do we start this conversation before they get rejected based on their record? We carve out a space for them to tell their stories in the profile, and put it front and center.

Life complexities often infect the lives of the previously incarcerated. By helping them share their life stories, we also reiterate on their life skills and capacity for hardships.

“Imagine a candidate who’s a 40-year-old, black single mom who graduated from college while working full-time. She probably knows some things about planning, resolve, multitasking, and stretching a quarter into a dollar. And I can make a good bet that she won’t give up.”

Source

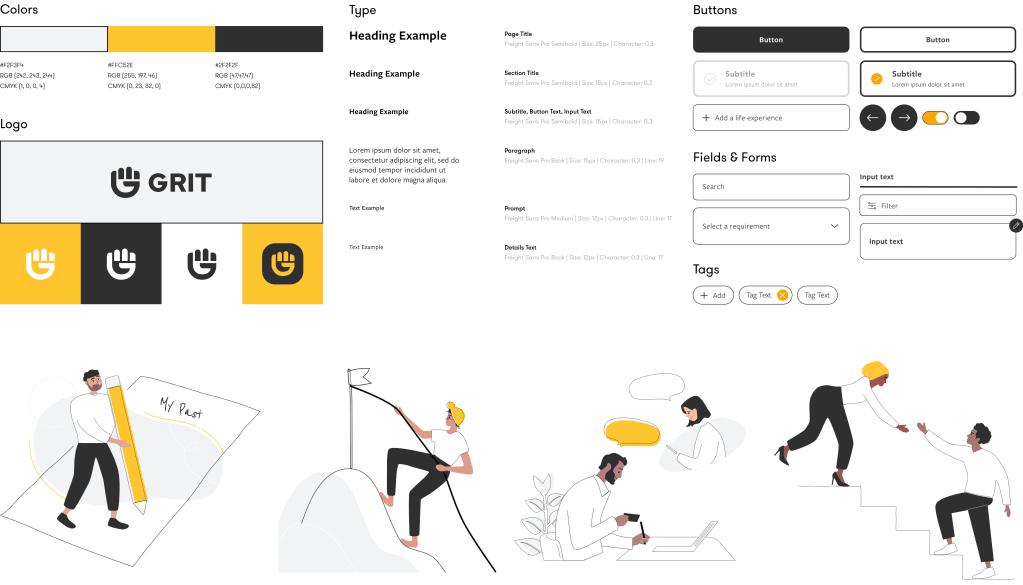

Visual identity: warmth and inclusivity

For the visual identity design, we underscored the mission of the brand: to provide strong, reliable support and a sense of belonging during the process of reintegration. We also empathized with the job seekers, understanding that searching for a job is already a daunting task that many of us dread. People with criminal records need even more encouragement and compassion to deal with the added prejudice. The objective was then to project a sense of warmth and embrace inclusivity.

The brand color is a saturated yellow, associated with energy, joy and hope. Complementing it with different shades of grey, we kept it simple to avoid distracting users from their tasks or overwhelming them in an already intimidating process.

For the logo, we played around with geometry, perspectives and negative space. The final design is the letter “G” pictorialized into a fist. Its minimalistic and rounded shapes are straightforward but welcoming. It captures the essence of a strong ally.

Sponge

Email:

hi@sponge.design

Copyright © 2024 Sponge Design Inc.